Article

PoliticsFrom Balance to Alignment: How the 1967 War Redefined U.S. Foreign Policy in the Middle East

Published on June 08, 2025

By: Ziad Hariri

Share This

Font Size

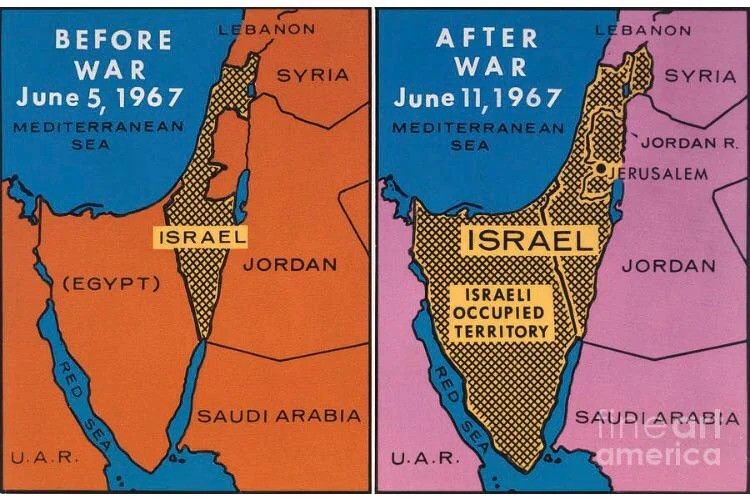

In June 1967, the United States crossed a strategic threshold in the Middle East. While the Six-Day War unfolded on the battlefield between Israel and its Arab neighbors, a quieter, yet equally consequential, transformation was taking place in Washington. U.S. foreign policy, long defined by a cautious balancing act between regional actors, tilted decisively in favor of Israel. The war didn’t just redraw borders in the region—it redrew Washington’s map of interests, alliances, and long-term commitments.

On the 58th anniversary of the Six-Day War, this article re-examines the 1967 conflict not merely as a military showdown or an ideological collapse for the Arab world, but as the pivotal moment when the United States recalibrated its Middle East strategy—abandoning neutrality in favor of explicit alignment. The result was a U.S.-led regional order that endures to this day, anchored in military aid, peace-brokering, and conditional partnerships—all rooted in the strategic conclusions drawn in the aftermath of June 1967.

Before the Shift: A Balancing Act in a Divided Region

Throughout the 1950s and early 1960s, American foreign policy in the Middle East was shaped by Cold War anxieties, oil security, and attempts to contain Soviet influence. The Eisenhower and Kennedy administrations maintained ties with both conservative monarchies and revolutionary Arab republics, all while seeking to avoid direct entanglement in Arab-Israeli disputes.

Egypt’s Gamal Abdel Nasser—icon of Arab nationalism—was viewed with growing suspicion in Washington due to his alignment with Moscow, opposition to Western military alliances, and vocal support for anti-colonial movements. Yet, the U.S. refrained from total confrontation, hoping to temper Nasser’s ambitions through diplomatic pressure and selective arms deals.

That caution ended in June 1967. As regional tensions escalated—with Egypt blockading the Straits of Tiran and Israel preparing for preemptive action—the Johnson administration began to see Israel as a more dependable pillar in an increasingly unstable region.

War as Watershed: Israel’s Victory, America’s Recalibration

The Six-Day War began on June 5, 1967. In less than a week, Israel seized the Sinai Peninsula, Gaza Strip, West Bank, East Jerusalem, and the Golan Heights. The speed and decisiveness of the Israeli military action stunned the world—and reshaped Washington’s perception of regional power.

President Lyndon Johnson, though cautious about direct U.S. involvement, had already shown rhetorical support for Israel, condemning the Egyptian blockade and drawing symbolic parallels between Israel’s struggle and the American tradition of fighting for survival on a hostile frontier. More critically, Johnson’s administration had quietly assured Israeli leaders that the U.S. would support their defensive actions-provided they did not initiate hostilities publicly.

Behind the scenes, the CIA was confident in Israel’s military superiority and reportedly shared this assessment with Israeli counterparts. Though the U.S. denied direct military involvement, many Arab governments believed that America had given Israel a "yellow light." This perception became a defining feature of Arab-U.S. relations for decades.

The New Doctrine: From Equidistance to Strategic Alignment

After the war, the United States dropped any pretense of even-handedness. Johnson articulated five core principles for a postwar settlement, a framework that would become the foundation for a decades-long U.S. policy of conditional diplomacy centered on Israel’s security interests. These principles were later reflected in UN Security Council Resolution 242, but crucially, Johnson made clear that Israel would not be forced to withdraw from occupied territories without a peace agreement.

This stance marked the dawn of a new U.S. doctrine: security guarantees for Israel, strategic aid to Arab allies conditioned on alignment with U.S. objectives, and a shift from containment of Soviet influence to the active shaping of the regional order.

In the years that followed, Washington deepened ties with Israel through military assistance, diplomatic backing, and defense cooperation. Egypt and Jordan, both humiliated in the war, would eventually move closer to Washington-especially after the 1973 war-forming the pillars of an emerging pro-American bloc.

Arab Disillusionment and Intellectual Crisis

The U.S. strategic realignment had broad consequences across the Arab world. Nasser, once a towering figure of resistance, suffered a devastating blow to his credibility. While he remained in power until September 1970, the defeat signaled the end of Pan-Arabism. Arab unity proved illusory, and Washington’s support for Israel emboldened conservative regimes wary of Nasser’s revolutionary message.

Beyond military defeat, the Arab public experienced a profound psychological and ideological shock. The failure of nationalist regimes to prevent territorial loss or defend Palestinian rights sparked waves of introspection and critique. Intellectuals across the Arab world-from Beirut to Cairo-began to question the viability of Pan-Arabism, the military-first strategy, and the very foundations of political legitimacy. This post-1967 soul-searching catalyzed a shift toward Islamic political movements, Marxist resistance thought, and new forms of Arab cultural critique.

Palestinian factions responded by breaking away from the Arab state-centric framework. Groups like Fatah and later the PLO embraced armed struggle and sought independent agency. The failure of Arab regimes to protect Palestinian interests gave rise to a new nationalist militancy-and eventually, to the political centrality of the Palestinian cause in Arab identity.

In Egypt, Nasser’s successor President Anwar Sadat would shift the country’s ideological compass. Facing severe economic stagnation, a demoralized military, and mounting public frustration after the 1967 defeat, Sadat recognized the need for a new strategic orientation. He distanced Egypt from Soviet patronage, expelled Soviet advisors, and recast Egypt as a partner in a U.S.-led regional order-culminating in the 1979 Camp David Accords.

The Long Arc of 1967: From Strategic Pivot to Permanent Alignment

What began as a Cold War-era recalibration became a defining principle of U.S. Middle East policy. Since 1967, every American administration—Democrat or Republican—has upheld the special relationship with Israel. At the same time, U.S. foreign policy has increasingly favored bilateral arrangements with Arab states over multilateral Pan-Arab frameworks.

This strategic tilt has outlived the Cold War, adapted to the War on Terror, and weathered the Arab Spring. From arms sales and security pacts to normalization agreements like the Abraham Accords, the legacy of 1967 lives on in America’s unwavering commitment to shaping the region on its own terms.

As historian Steven Spiegel observed, “Before 1967, efforts to resolve the Arab-Israeli conflict were subordinate to regional priorities. After 1967, the conflict became central to American policy in the region.”

The War That Redrew the American Map of the Middle East

The Six-Day War was not just a regional catastrophe for the Arab world-it was a global strategic turning point for the United States. What began as a defensive posture became a long-term commitment to regional engineering, alliance management, and strategic favoritism.

In the rubble of Nasser’s Pan-Arabism, the United States found a new blueprint: a divided region, anchored by military aid, propped up by selective diplomacy, and increasingly dependent on American brokerage. That framework still defines U.S. policy today.

To understand the present contours of American influence, we must return to 1967. It was not just the year Israel redrew regional borders. It was the year America redrew its own.

Share This

Contact

If you have any query about our service please contact with us

- +961 3 727 636

- infore-co-de.com

Popular Articles

June 09, 2025

اللامركزية الإدارية في لبنان: مسار الإصلاح، التحديات، وآفاق التطبيق

By Ziad Hariri

August 17, 2025

Lebanon’s Last Chance: Disarming Nonstate Actors in a Post-War Transition

By Ziad Hariri

August 21, 2025

Power and Interests: Mapping U.S., Chinese, and Russian Strategies in the Middle East and North Africa

By Mohamad Fawaz